Real Raising from the Dead or Fake News

Around 1960, in the Republic of Congo, a two-year-old girl named Thérèse was bitten by a snake. She cried out for help, but by the time her mother, Antoinette, reached her, Thérèse was unresponsive and seemed to have stopped breathing. No medical help was available to them in their village, so Antoinette strapped little Thérèse to her back and ran to a neighboring village.

According to the US National Library of Medicine, brain cells start dying less than five minutes after their oxygen supply is removed, an event called hypoxia. After six minutes, the lack of oxygen can cause severe brain damage or death. Antoinette estimates that, given the distance and the terrain, it probably took about three hours to reach the next village. By the time they arrived, her daughter was likely either dead or had sustained significant brain damage.

Antoinette immediately sought out a family friend, Coco Ngoma Moyise, who was an evangelist in the neighboring village. They prayed over the lifeless girl and immediately she started breathing again. By the next day, she was fine—no long-term harm and no brain damage. Today, Thérèse has a master’s degree and is a pastor in Congo.

When I heard this story, as a Westerner I was naturally tempted toward skepticism, but it was hard to deny. Thérèse is my sister-in-law and Antoinette was my mother-in-law.

According to the US National Library of Medicine, brain cells start dying less than five minutes after their oxygen supply is removed, an event called hypoxia. After six minutes, the lack of oxygen can cause severe brain damage or death. Antoinette estimates that, given the distance and the terrain, it probably took about three hours to reach the next village. By the time they arrived, her daughter was likely either dead or had sustained significant brain damage.

Antoinette immediately sought out a family friend, Coco Ngoma Moyise, who was an evangelist in the neighboring village. They prayed over the lifeless girl and immediately she started breathing again. By the next day, she was fine—no long-term harm and no brain damage. Today, Thérèse has a master’s degree and is a pastor in Congo.

When I heard this story, as a Westerner I was naturally tempted toward skepticism, but it was hard to deny. Thérèse is my sister-in-law and Antoinette was my mother-in-law.

By contrast, in February, a video of South African preacher Alph Lukau drew widespread attention for what appeared to be someone raised from the dead in his church. Lukau claims he simply prayed for the unconscious man in the coffin, but regardless of who is responsible, the situation was clearly designed to deceive. The coffin was purchased from one funeral parlor by customers allegedly posing as workers from another funeral parlor, and the hearse was borrowed from yet a third. Critically, none of the funeral parlors ever saw the body of the supposed deceased.

The video of this apparent resurrection was quickly unmasked, and Lukau was condemned by numerous African church leaders. Nevertheless, questions and concerns remain.

Thérèse (right), with her mother, Antoinette (middle), and the author’s wife, Medine (left).

I’m married to an African, have spent time teaching in Africa, and count many African Christians as relatives and friends. I’ve learned much from them and their approach to miracles challenges me in good ways. African Christianity has a tradition of prophetic leaders, and there is great respect among Africans across the continent for a “man of God.” But because miracles draw crowds, many leaders compete in miracle narratives. The internet democratizes access, so leaders who publicly demonstrate their miracle prowess can become wildly successful. Churches can control the setting and potentially any staging. The opportunity for fakery abounds and my miracle-believing, African Pentecostal friends lament the spread of fraudulent miracle-workers. Is there a way we can distinguish between fabricated miracle reports and the genuine article?

Misplaced cynicism

Christians use the word miracle in different ways. Because we believe that God works through his creation, we are right to thank God for recoveries from sickness or injury, dramatic or not. When we offer thanksgiving for a successful surgery or an effective immune system, we don’t need to claim it happened only by miraculous means.

Neither should we limit the term exclusively to what lacks possible natural causes. The Bible says that God parted the Red Sea using a strong east wind that blew all night (Ex. 14:21). But just because we recognize the natural components of this event, we would be wrong to conclude it was merely a fortuitous coincidence that allowed the Israelites to cross on dry ground.

So how can we evaluate popular accounts of miracles? When we don’t know the witnesses and lack other evidence, we have to live with varying amounts of uncertainty. But examining credible examples can help us understand how to approach miracles while being neither gullible nor faithless.

If some African Christians accept miracle claims too quickly, many of us in the secular West indulge the opposite cultural temptation. Our heritage of anti-supernaturalism, stemming from 18th-century Deists and the naturalist philosophy of David Hume, predisposes us to dismiss all miracles. That way, at least, we cannot be embarrassed by claims that turn out to be fraudulent.

Resurrection reports appear through much of church history. In the late second century, Irenaeus, for example, reproached Gnostics’ lack of miracles by noting an orthodox church in France where, he reported, raisings were frequent. Raisings were also among the documented miracles Augustine surveyed in book 22 of The City of God. John Wesley offered a firsthand account of an apparently dead man being revived through prayer, recorded on the day it occurred, December 25, 1742.

Most early 20th-century testimonies are impossible to verify today, but occasionally some evidence remains. For example, in 1907, one year after the beginning of the early Pentecostal Azusa Street Revival, the revival’s newspaper The Apostolic Faith reported the raising of one Eula Wilson, whose blindness was also healed in the process.

I was initially skeptical, but The Apostolic Faith cited its source, The Nazarene Messenger, another newspaper that recounted the same story but left out the healing from blindness. My first instinct was to suppose that The Apostolic Faith was embellishing the initial report. While such embellishments happen, in this case, The Nazarene Messenger also had a source, The Wichita Eagle. This report, from within days of the event itself, included testimony from the attending physician and included Wilson’s healing from blindness.

Some recent Western raising reports have become Christian films, such as those of Annabel Beam (Miracles from Heaven) and Baptist minister Don Piper (90 Minutes in Heaven). Both stories are inspiring but neither is triumphalistic: Beam experienced incredible suffering before her remarkable healing, and Piper suffered greatly along the road to recovery. If testimony is being used for fundraising or a particular minister’s glory, caution is the wiser instinct. But in cases like these, no obvious self-aggrandizing motive is in view.

Another raising film, Breakthrough, released this past Easter. Based on Joyce Smith’s book The Impossible, the film recounts the experience of Joyce’s teenage son John. Unable to revive John after the boy drowned, physician Kent Sutterer had abandoned hope when John’s desperate mother started praying. At that moment, John’s heart restarted. Doctors deemed his subsequent full recovery remarkable.

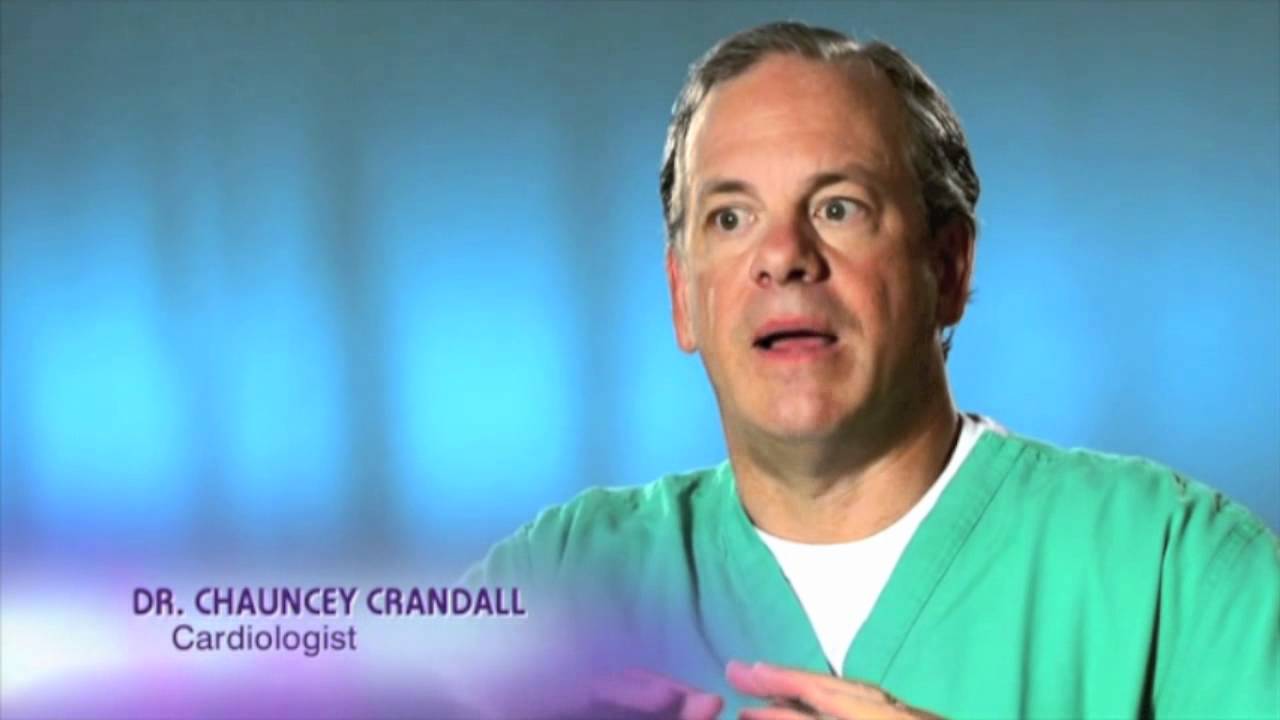

The witness of a medical professional like Sutterer further pushes against knee-jerk skepticism about raisings. Chauncey Crandall, a cardiologist in West Palm Beach, felt led to pray for a man who had already been unresponsive for some 40 minutes. Crandall assumed the man, Jeff Markin, was beyond help.

Although the death certificate had been signed and Markin’s extremities were already turning black, Crandall prayed aloud for Markin. Then he urged a colleague to shock Markin with defibrillator paddles one more time; after the jolt of electricity, Markin’s heart immediately began beating. Markin made a full recovery, became a believer in Christ himself, and now testifies alongside Crandall to what God did for him.

This is an impressive story, but it has some important context. This was not the first time Crandall had prayed for a raising. Previously, his own son, Chad, died from leukemia. Crandall prayed in faith for Chad’s raising. Chad did not revive. In the face of crushing disappointment, Crandall had to decide whether to distance himself from God or trust him no matter what. He chose the latter, and so he was ready when God called him to pray for Markin. And it’s not just that doctors witness raisings.

Sometimes, they are the ones raised. On October 24, 2008, Sean George, head of general medicine at Kalgoorlie Hospital in Australia, suffered a fatal heart attack. He was in cardiac arrest for an hour and 25 minutes and even flatlined for 37 minutes. His wife, also a physician, arrived and prayed for him and, abruptly, his heart restarted. After recovering, he returned to his medical practice. George has full medical documentation online.

Raisings in Africa

What about raisings reported outside the West? Are there credible African resurrection stories?

Lack of medical facilities in many locations makes miracles both more necessary and harder to document. Still, people in traditional cultures are often familiar with signs of death, such as rigor mortis or lack of pulse and respiration, because they are less insulated from it than Westerners are. So while we may not be able to say how dead a person was in a clinical sense, such cases still seem significant, whatever the terminology used to describe them.

One friend I worked with during my first three summers in Nigeria was Leo Bawa, a missions researcher who now holds a Ph.D. from the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. When I was conducting research for a book on miracles, I asked Bawa if he knew of any. “Not many,” he replied, before giving me seven pages of eyewitness accounts.

One experience, in particular, caught my eye: In a village where Bawa had been doing research, some non-Christian neighbors brought him their dead child, asking if he could help. He prayed for a couple of hours and then handed the child back to them alive. Reasoning it may have been a misdiagnosed death, I asked how often he prayed for dead persons. He said he had done so only one other time; he prayed for his best friend after his death, and the friend stayed dead. In this non-Christian village, however, Bawa believes God answered his prayer for the honor of Christ.

Other miracles seem to have happened without any prayer at all. I know Timothy Olonade from my time in Nigeria, a man who had a prominent scar that I never asked about. Years after I first met him, some mutual friends, including my doctor in Nigeria, told me Olonade’s story and I followed up with him.

In December 1985, Olonade was killed in a head-on traffic accident. After being pronounced dead in the hospital, he was sent to the morgue. Hours later, as a worker went in to move some bodies, he found Olonade moving. Dumbfounded, the doctor at the hospital expected that Olonade would at least have irreparable brain damage. But he fully recovered, something his maxillofacial surgeon described as miraculous. Now an Anglican priest, Olonade is a leader in the Nigerian missions movement.

Some stories have come to me unbidden. I was in an academic meeting with Ayodeji Adewuya, who has a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester when I shared some global miracle accounts. A few Western professors in the meeting understandably questioned me, then Adewuya stood up and shared his own experience. His son was pronounced dead at birth in 1981. After half an hour of prayer, however, the child was restored with no brain damage. This same son now has a master’s degree from University College of London and another from Cornell.

My wife is from the Republic of Congo (the smaller of the two African countries named Congo) and I’ve interviewed her friends and family with credible accounts, frequently corroborated by multiple, independent witnesses.

Take, for instance, the story of Albert Bissouessoue. A deacon in the Evangelical Church of Congo, Bissouessoue is my wife’s brother’s father-in-law. When he was a school inspector in Etoumbi, in the north of Congo, people knew him as a strong Christian. A crowd brought to his residence a girl’s body, reporting that she died some eight hours earlier. They had taken her first to traditional practitioners, who sacrificed animals and smeared blood on her in vain attempts to revive her. After reproaching them for not coming first to the living God, Bissouessoue prayed for half an hour, and the child revived.

As you might expect, this caused quite a stir in Etoumbi. So, when another child died, people came looking for Bissouessoue. Unfortunately, he was out of town, so they drafted his wife, Julienne, to pray. When she prayed, this second child revived immediately. Julienne herself was shocked, reporting that God simply gave her faith at that moment. When I asked Albert and Julienne if they had ever prayed for anyone else who was dead, they reported that these were the only two occasions. They consider it something special that God was doing for his witness in that community. And of course, there is the story from my own mother-in-law and sister-in-law, Antoinette and Thérèse. Because of how well I know them, their story, more than any other account, forced me to reconsider my Western cynicism.

The place of miracles

The antidote to false miracle claims is not to reject miracles altogether. We must take care when we hear of (or even experience) a miraculous event that we neither accept all miracles as true nor dismiss them all as fake. The reality is much more complex.

But how do we exercise the appropriate amount of caution? While no formula allows us to verify all miracle stories, I have noticed a pattern.

Fraudulent miracles tend to flourish where they profit their purveyors. This is what we see in the Lukau story from South Africa. Yes, some Christians downplay miracles too much, but others need to stop exalting them as the highest ministry or as a sign of divine approval, especially where leadership and teaching are concerned.

When Paul lists spiritual gifts in 1 Corinthians 12:28, he actually ranks teaching higher than miracles. The Greek text of Ephesians 4:11 links pastors with teachers and the Pastoral Epistles make teaching ability a prerequisite for ministry (1 Tim. 3:2, 2 Tim. 2:24, Titus 1:9). Miracles are nowhere a biblical requirement (or necessary endorsement) for ministry. Someone might even have a gift of miracles but not be a good teacher. One can have both kinds of gifts (Acts 19:9–12), but one does not necessarily entail the other.

By contrast, credible dramatic signs are most frequent where the gospel is breaking fresh ground—as in the Gospels and Acts. In these situations, the miracles tend to advance the cause of faith, not the will or needs of a particular person or group. Miracles are a wonderful foretaste of the coming kingdom. Thus Jesus’ exorcisms revealed the kingdom’s nearness (Luke 11:20), and Jesus describes his healings in language that invokes Isaiah’s description of the ultimate restoration (Luke 7:22). Nevertheless, the kingdom’s fullness remains the future. Even genuine gifts are limited: Paul says that we know in part, and we prophesy in part (1 Cor. 13:9).

When God acts in our lives, we should testify about it, but when possible we should also offer verification. If Jesus urged a leper to follow the scriptural prescription to verify his healing with a priest (Mark 1:44), it is appropriate for us to verify miracles when possible. This way open-minded people who do not know the witnesses well enough to take their word for it can still experience the awe of seeing God at work.

Additional layers of evaluation help. For example, false teachers often exploit people for money (Jer. 6:13, Micah 3:11, 2 Pet. 2:3) and tell them whatever they want to hear (2 Tim. 4:3–4). Jesus warned us to discern prophets by their fruits, not by their gifts (Matt. 7:15–23). What is the outcome of a particular miracle? God’s gifts are good, but their main purpose is building up Christ’s body, not our reputations (note 1 Cor. 12–14). Most of Jesus’ miracles, such as healing sickness, expelling spirits, and stilling storms, demonstrated compassion as well as power.

Moreover, genuine gifts should honor Jesus (1 Cor. 12:3, 1 John 4:1–6). The Book of Acts shows that Jesus’ name should get the credit for miracles because they attest to his gospel, not the miracle worker (Acts 3:12–13; 14:3).

Indeed, Scripture offers many examples of those gifted by God’s Spirit who was disobeying God, such as Balaam and Samson. One of the most striking examples is Saul, who, on an errand to try to kill David, ended up falling down and prophesying. This was not because Saul was godly, but because God’s Spirit was strong in that place (1 Sam. 19:20–24).

Not every claim to a miraculous raising today is authentic. Everywhere in the world, most people who die stay dead. Even those resuscitated miraculously, such as Lazarus, die again; all healing in our mortal bodies is by definition temporary. Such miracles do, however, remind us that Jesus Christ, who raised the dead during his earthly ministry, is the risen and exalted Lord. Sometimes he continues to grant signs of the future, reminders of the resurrection hope that in him awaits us all.

Craig Keener is F. M. and Ada Thompson Professor of Biblical Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary. His most recent book is Galatians: A Commentary from the New Cambridge Bible Commentaries series (Baker Academic, 2019).