Moral Absolutes exist?

It is grossly inconsistent for philosophers to argue that there are no moral absolutes when everything physical that can be observed and measured is clearly and undeniably regulated by absolute and inviolable laws—apart from which even the smallest organism or subsystem in our vast and intricate universe could not operate.

Even the ancient Greeks recognized that there was a standard of right and wrong, a basic kind of moral sowing and reaping. According to their mythology, the goddess Nemesis sought out and punished every person who became inordinately proud and arrogant. No matter how much they might seek to evade her, she always found her victims and executed her sentence.

The Bible elucidates absolute moral law very clearly and frequently. For example, God had “granted sovereignty, grandeur, glory, and majesty to Nebuchadnezzar,” but because of the king’s arrogant pride, the Lord deposed him from the throne and made him become like a wild animal that ate grass.

“Yet you, his son,” Daniel declared before Belshazzar during the great banquet in Babylon, “have not humbled your heart, even though you knew all this, but you have exalted yourself against the Lord of heaven; and they have brought the vessels of His house before you, and you and your nobles, your wives and your concubines have been drinking wine from them; and you have praised the gods of silver and gold, of bronze, iron, wood and stone, which do not see, hear or understand.

But the God in whose hand are your life-breath and your ways, you have not glorified. That is why:

“the hand was sent from Him, and this inscription was written out,” the prophet went on to explain, an inscription whose interpretation was: “God has numbered your kingdom and put an end to it.… you have been weighed on the scales and found deficient.… your kingdom has been divided and given over to the Medes and Persians” (Dan. 5:18–28).

The modern world has its own Belshazzar's.

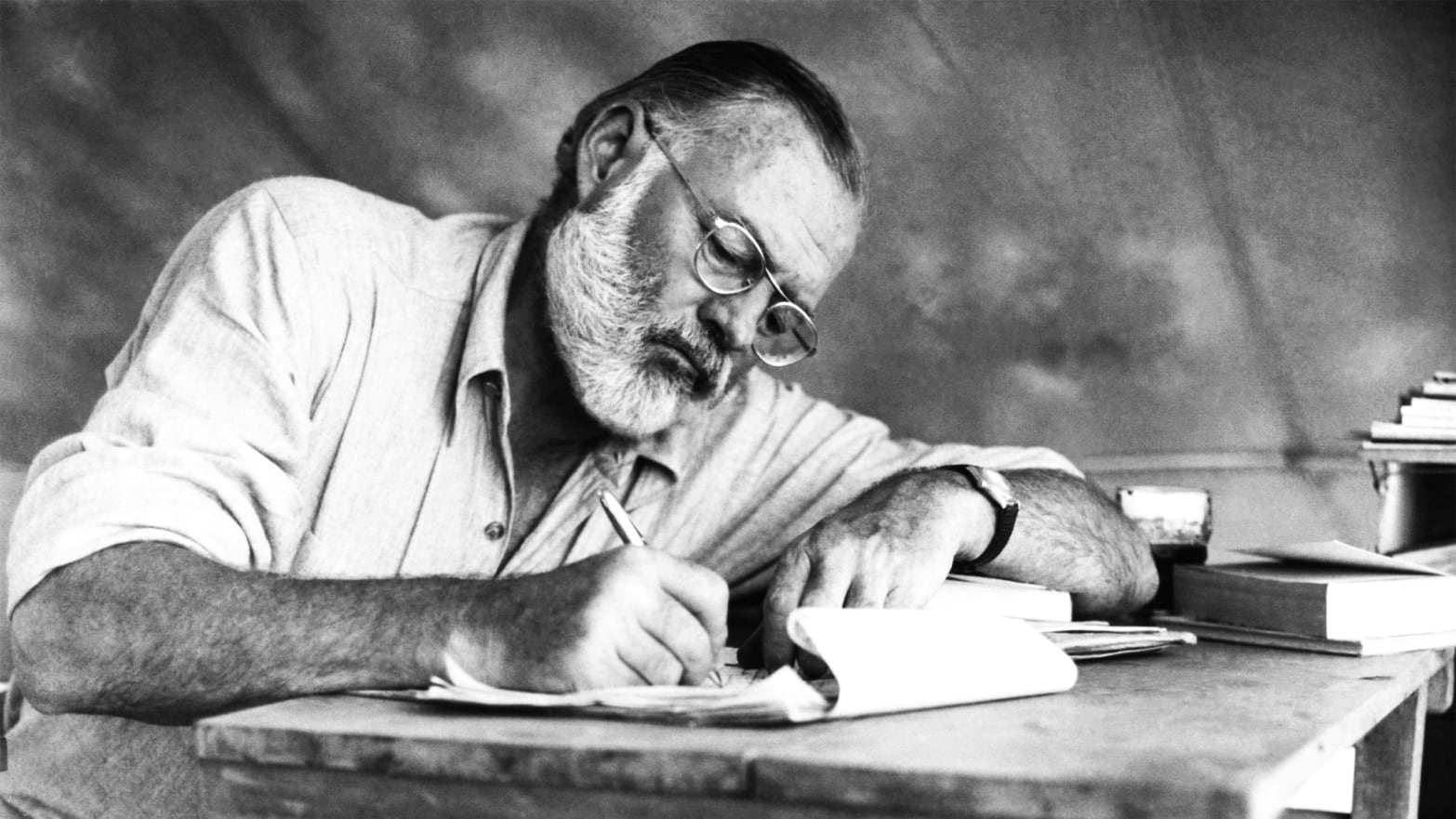

Ernest Hemingway became famous for snubbing his nose at morality and at God, declaring that his own life proved a person could do anything he wanted without paying the consequences. Like many others before and after him, he considered the ideas of the Bible to be antiquated and outdated, completely useless to modern man and a hindrance to his pleasure and self-fulfilment.

Moral laws were to him a religious superstition that had no relevance. In a mocking parody of the Lord’s Prayer he wrote, “Our nada [Spanish for “nothing”] who art in nada.”

But instead of proving the impunity of infidelity, the end of Hemingway’s life proved the folly of mocking God. His debauched life led him into such complete despair and hopelessness that he put a bullet in his head.

/sinclair-lewis-3271293-5c50bcd1c9e77c00016f380d.jpg)

Other famous authors, such as Sinclair Lewis and Oscar Wilde, who openly attacked the divine moral standard and thumbed their noses at God, mocking His Word and His law, were nonetheless subject to that law.

Lewis died a pathetic alcoholic in a third-rate clinic in Italy, and Wilde ended up an imprisoned homosexual, in shame and disgrace. Near the end of his life he wrote,

“I forgot somewhere along the line that what you are in secret you will someday cry aloud from the housetop.”

Until the last days, there will continue to be “mockers, following after their own ungodly lusts” (Jude 18). But their “end is destruction, whose god is their appetite, and whose glory is in their shame” (Phil. 3:19).

In every dimension, including the moral and spiritual, the universe is structured on inexorable laws. In Galatians 6:7–10, Paul uses a well-known law of botany—that a given seed can reproduce only its own kind—to illustrate God’s parallel and equally inviolable laws in the moral and spiritual realms.

Author: MacArthur, J. F., Jr. (1983). Galatians (pp. 184–185). Chicago: Moody Press.