Two rocks stars and their Christian journey

“It’s impossible to meet God with sunglasses on” — Bono

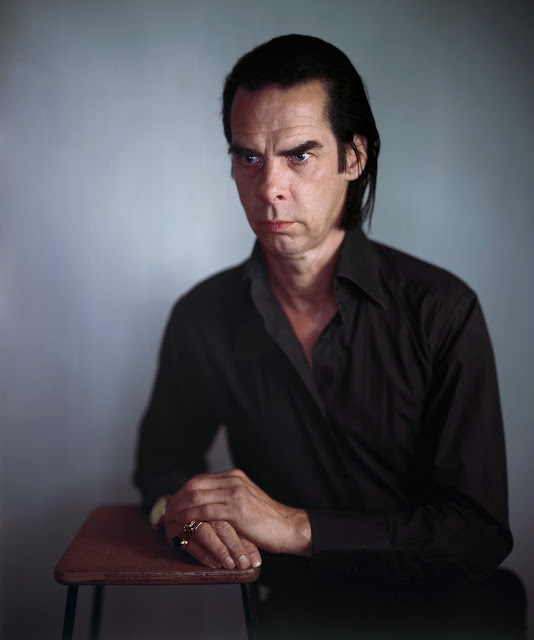

“Hope is optimism with a broken heart” — Nick Cave

Two rock music world’s most enduring frontmen have published long, exploratory memoirs in the lead-up to Christmas. Nick Cave’s Faith, Hope and Carnage record conversations with journalist Seán O’Hagan during the lockdown months of 2020. The epigraph to the book is a biblical quote from the Old Testament book of Isaiah: “A little child shall lead them.” Bono’s nearly 600-page book, Surrender, is a reflective journey through his life in music, beginning and ending with his birth — in fact, the penultimate chapter is a poetic imagining of his own entry into the world.

For these famous rockstars, both books read like adult Sunday school lessons. Both artists see their art and lives intertwined with the Christian faith's spirit, history, and eschatology. Both were “catechised” in different ways as teenagers, endured significant trauma in their personal lives at similar times, and have been “paralysed by the blood of Christ” ever since. If you thought rock had left God outside the backstage door, these books would be a surprise.

Bono is the believer, turned on to God as a youth-group teenager and still ignited by the unique story of Jesus of Nazareth: “If I was in a cafe right now and someone said, ‘Stand up if you’re ready to give your life to Jesus’, I’d still be the first to my feet.” Nick Cave is of a different ilk — rebellious, angry, and until recently cynical — although he too had a churched upbringing, famously singing in the choir at Wangaratta’s Holy Trinity Cathedral at the age of nine. And his journey to or from faith has been a constant theme in his creative work.

The titles of the books are important. Irish Bono’s is a direct antagonism to Ulsterman Ian Paisley’s booming preacherly cry of “No surrender!” as he opposed any peace agreements in Ireland until 2007 when negotiations with Sein Finn’s Gerry Adams led to relative peace between Protestants and Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland.

But it is also a cry of metaphysical surrender in the face of “the immortal invisible”, whom Bono cheekily adds to his acknowledgements. Bono’s “surrender” has been ringing out in various ways since he flew a white flag at their famous Red Rocks concert in 1983.

Cave book’s title is likewise antagonistic, this time riffing against the Pauline injunction that “faith, hope and love” remain in the world while we await the return of Christ (a phrase from 1 Corinthians 13).

For Cave, it is “carnage” in the form of family tragedies that have gradually, and then suddenly, brought him to his knees. In fact, both authors identify the Pauline priority of love as the goal towards which their personal projects are headed. And both see “surrendering” as a key to finding that love. Submit, surrender, let God be God, and recognise a higher power. These are the concluding observations of two of the most famous musicians of the past forty years. It’s not very rock and roll.

The proper analogue to Cave’s book is Michka Assayas’s 2005 book, Bono on Bono, which follows a very similar conversation pattern and is largely about faith questions. In the Foreword, Bono writes that he engaged in the conversation with Assayas as therapy because his wife told him he hadn’t dealt with the death of his mother (she died when he was 14 after collapsing with a stroke at graveside while her own father was being buried).

Nick Cave describes the death of his son Arthur, also at 14, as the turning point of his life. “Arthur’s death literally changed everything for me. Absolutely everything. It made me a religious person …” So therapeutic, thanatic dialogue it is. The insistent reality of death and the question of what lies beyond has become an irresistible force in both men’s creative work and their approaches to life overall. Bono writes:

Everything we do, think, feel, imagine, and discuss is framed by whether our death is the end or the beginning of something else. It takes great faith to have no faith. The great strength of character to resist the ancient texts that suggest an afterlife.

Bono’s memoir is not entirely coherent, but which authentic memoir is?

It’s like sitting in a room listening to your favourite cousin (who definitely snogged the Blarney Stone) pouring out his thoughts. If that doesn’t appeal to you, you probably aren’t a U2 fan because the music and life are intermingled. Every chapter is a U2 song title, suggesting the reciprocal relationship between art-making and living — it’s hard to know which.

The 40 chapters (“40” is itself a U2 song title, for a song that is a re-imaging of Psalm 40 from the Hebrew Bible) traverse Bono’s life, racing back and forwards in time, always intent on letting us in a little more to his mind, his world, his anxieties.

There’s always something pleading in Bono’s voice, trying desperately to connect with us, the readers, hoping we (or Whoever is listening) might have something to give in return.

After all, as Bono writes, “Songs are my prayers.” This intimacy is intensified in the audiobook version, which features clips of re-worked U2 songs, apparently from a forthcoming album, Songs of Surrender. Bono reveals that the band prays before every show, asking that they will be “useful … to music … to some higher purpose.”

Maybe that’s what rock and roll are for. But Bono claims the band has “broken the promise at the very heart of rock and roll” by continuing to be useful for 35 years rather than collapsing in a splendid implosion of decadence and indulgence.

Bono: A long obedience in the same direction

There’s no mistaking that Bono’s memoir is that of a convicted Christian. Laced with Bible passages, especially stories that Jesus told, his life has what the theologians call a cruciform shape: he believes Jesus’s sacrifice for sins and resurrection from the dead are the central events of human history, and he sees his own journey as a “surrender” to that cosmic truth: “I’ve never left Jesus out of the banalest or profane actions of my life.”

But just when the reader feels a little proselytised, Bono saves things by returning to domestic life, regaling anecdotes about his friends and their eccentric adventures, earthy and enjoyable lyrics with a serious divine backing track.

Even the Christocentric discussion gets this vernacular undermining. Their creative director, Willie Williams, exemplifies this as they discuss some staging: “Why don’t you just build a big f-ing cross at the centre of the arena. That’s what you really want to say. Am I right?”

I hadn’t quite fathomed just how many of Bono’s songs are about his childhood. And not just the old stuff — albums with giveaway titles such as “Boy” and songs like “I Threw a Brick Through a Window” — but many of their recent material, too.

And back in that childhood, Bono found a friend in Jesus. In fact, he recounts this in almost mawkish simplicity late in the book when, during a therapy session, he realises that his deepest image of safety is walking alongside a river with Jesus.

Bono named his firstborn daughter Jordan after the river in Israel where Jesus was baptised. He highly values childlikeness and plays as both proper expressions of human creatureliness and a means to access creativity.

More than once, he invokes Jesus’s teaching that a person must “enter the kingdom of heaven as a child” with the trust, naivety and dependence that entails. As he sings in “Stand Up Comedy”, “the right to be ridiculous is something I hold dear.”

The dad’s jokes, the foolish stagecraft, the costumes and the cheekiness: all have roots in a theology of sovereign care. His belief in a “good father” God into whose plans for the universe he has a place is liberating and means he can play happily without fear of failure or reprisal. Theologians call it divine comfort.

The phrase “a long obedience in the same direction” is usually associated by Christians with the writer Eugene Peterson, one of Bono’s favourite believers. As well as penning a popular paraphrase of the New Testament called The Message, Peterson wrote a book with that lengthy title.

However, the phrase comes from Nietzsche, who used it to describe the task of the godless Stoics if they are to affect any power over the world: persevere, dominate, concentrate, and overcome.

- Peterson, however, deploys it as the best way to describe the Christian life: keep being Jesus-like, remain faithful, and seek the kingdom of God.

- Peterson found great pleasure in imagining Nietzsche’s fury at the appropriation of his phrase, and I think Bono enjoys the same inversion.

Bono loves the “Road to Emmaus” story from the Bible, in which, after his resurrection, Jesus appears incognito to some of his followers. Bono loves the drama of this account and the idea that you need to be open to whatever and whoever is in front of you — they just might hold the key to unlocking your troubles.

In fact, the book contains several pilgrimages, either to sites of musical fame or of metaphysical importance. Bono recounts visiting Israel, profoundly moved by the significance of Jesus’s acts and teaching there. It also recounts the band’s “desert sojourn” across America, where they pause at the famous Joshua Tree, which arguably became the central image of their breakthrough album. In fact, Bono’s vision of Christian discipleship is that it is a pilgrimage.

He famously describes his journey as “a pilgrim’s lack of progress”, and in a chapter praising St. Paul, who had an experience of the risen Christ on a journey on the ancient road to Damascus, Bono writes, “There is no promised land. Only the promised journey, the pilgrimage.”

Bono’s memoir is delightfully and astonishingly down-to-earth for a person who has been famous since his early twenties. It is mostly a diary-style, conversational recounting of his family life, the band's development, and his thoughts on love, marriage, friendship, making music, politics, poverty … and faith.

The faith dimension runs deep, and it’s natural, not some odd overlay on a rockstar’s reality. Faith came early to Bono, in his teenage years, with a Pentecostal youth group intensifying what he knew from his mixed Catholic-Protestant parentage (his father Roman Catholic, mother Protestant).

He is very open about the depths of his Christian faith but equally open about not living up to the way of Christ: “I’m a follower of Christ who can’t keep up. I can't keep up with the ideas that have me on the pilgrimage in the first place.”

One of the problems for a book like this is that all the true fans already know most of the stories, and all the new readers have to catch up with what is happening.

Unexpectedly, the book’s central intention is the re-assertion of the normality and goodness of Christian commitment. Bono would never put it like that, which is why people admire him. His capacity to be a normal secular-age human being in the public eye, and then a lifelong Christian devotee alongside that, is one of the reasons he still gets a hearing. “Am I bugging you? I don’t mean to bug you”, he once sang.

The level of fame on display in his memoir is preposterous (just imagine introducing your father backstage to Diana, Princess of Wales, at Pavarotti’s invitation), but Bono’s gift is to let you as the reader into the room with the superstars and be as surprised about it all as you are. It’s driven by personality — he’s a natural empath — but also Christian humility about yourself and the equal value and significance of others.

Nick Cave: Window shopping and the doorway of faith

Perhaps surprisingly, Cave’s book is the more spiritually exploratory of the two — by design since it is a conversation around faith. His artistic work began with the seminal Melbourne post-punk band, The Birthday Party, and he has nearly fifty years of creative output. That work is replete with themes of God, religion, fallenness, and divine love. But there is something of a “turning”, as Tim Winton might call it, in the conversation with Seán O’Hagan.

While Cave’s work has always been biblically intertextual, drawing on the characters, themes, and often the style of biblical books, it could be considered as performative in nature up until the album “The Boatman’s Call”. The concerts were like religious experiences but more parodies of those experiences. But in recent years, there has been a contemplative dimension to the new work, a willingness to be vulnerable before the divine.

Cave’s religious impulses and interests have always been Christian rather than more broadly spiritual, which needs to be accepted rather than diminished by critics. “I’m not really that interested in the more esoteric ideas of spirituality”, he says. “I’m particularly fascinated with the Bible and, in particular, the life of Christ.”

In fact, the traditional Christian teaching around personal sin and the need for forgiveness have become pressing for Cave: “I believe that what I have done is an offence to God and should be put right in some way.” It’s a focus that recurs throughout his conversation with O’Hagan.

In his piece on Cave’s religiosity in the collection Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave, Robert Eaglestone notes that Cave’s prosopopeia, his mask of performance, has always involved this Christian preacher or evangelist type. Eaglestone also observes that this division between the performed and the private is starting to break down for Cave.

Religious sensibility and religious rhetoric are starting to merge. In the same volume, Lyn McCredden invokes Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection to explore Cave’s regular entangling of the erotic and the sacred, human love in extremity and divine love in extremity, to characterise Cave’s peculiar religiosity.

Cave shocks the listener who hears a song such as “There is a Kingdom” — which could be sung in church — and thinks he has “turned to God” by also writing songs that appear to celebrate rape and murder (he and Warren Ellis recently composed the soundtrack for the Netflix series on serial killer Jefferey Dahmer). McCredden notes that this meeting of violence and love is precisely where genuine religious encounter occurs:

In the blackness of Cave’s imagined world — its violence and bloodletting, its despising and yearning denizens, its often tragic eroticism — his characters are not “swallowed up”, finally. They emerge — stagger forward, wander sadly to your door, insisting on telling you their tale of loss or threat, seduce you with their longing — clothed in both flesh and spirit.

But the “new” Nick Cave seems to be melding together the performer and the preacher, the artist and the believer. The Cave that people hear from the stage, increasingly in spoken word form, and the Cave who writes the astounding and spiritually edifying Red Hand Files in response to fan’s questions, appears not be wearing a mask.

Part of Cave’s “turn” seems to involve acknowledging the utility of faith: faith works to increase well-being and provide meaning and purpose for most people. Cave discusses his experience with Narcotics Anonymous and the practical help it provides for people to acknowledge the possibility of a higher power than themselves.

“I guess what I’m saying”, Cave explains, “is that believing itself has a certain utility — a spiritual and healing benefit, regardless of the actual existence of God.” This seems to represent a current position for Cave on matters of religion: it is personally and creatively useful and might border on something close to true but remains elusive. He contemplates a leap of faith:

I think of late I’ve grown increasingly impatient with my own scepticism; it feels obtuse and counterproductive, something that’s simply standing in the way of a better-lived life. I feel it would be good for me to get beyond it. I think I’d be happier if I stopped window-shopping and just stepped through the door.

Nick Cave turns up half a dozen times in Bono’s book, always admiring a lyric or quality in the artist. The favour is not returned by Cave, but I don’t know that much can be made of that.

Bono has a great gift for affirming others; much of his book does just that. As he recounts stories, he inevitably casts his co-conspirators in their best light, highlighting how much he admires them (sometimes to the point where it feels a little unbelievable). Pushing others forward seems to cost Bono nothing; he has no “tall poppy” syndrome to speak of.

Whether it is an old school teacher or former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Bono seems driven to see the best in people and give them their dues. In his book Killing Bono, old school friend and accomplished journalist Neil McCormick writes about his envy of Bono’s life, offset by Bono’s kindness in always remembering him: “Rock stardom couldn’t have happened to a nicer, and, frankly, more deserving guy. He’s certainly put it to a lot better use than I ever would have.”

Both men return regularly to the debt they owe their wives. While Cave’s relationships make a more complex story than Bono, who has been married to his childhood crush since he was 21, both are acutely aware of the sacrifices made by spouses and the benefits of the family life they supported. It’s quite a conservative position that both men have reached in their sixties: committed marriages with close families.

“It’s a lower temperature take on romantic life”, Bono writes, “but it’s enduring. I have been so fortunate.” And Cave credits the shared grieving experience he has with his wife Susie over their lost son as how an affirming and grateful view of life has emerged: “We survived because we remained together … We can collapse together, or apart, in the knowledge that tomorrow we will be back on our feet. I know that mostly I am happy and life is good.”

ABC Australia Religion and Ethics