Scientism can't generate moral values

|

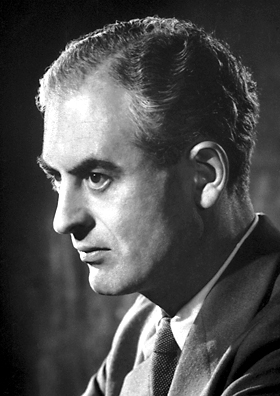

| Peter Medawar (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

To be an empiricist is to withhold belief in anything that goes beyond the actual, observable phenomena, and to recognize no objective modality in nature. To develop an empiricist account of science is to depict it as involving a search for truth only about the empirical world, about what is actual and observable … it must invoke throughout a resolute rejection of the demand for an explanation of the regularities in the observable course of nature by means of truths concerning a reality beyond what is actual and observable.

This emphasis on what’s ‘actual and observable’ gives the sciences their distinct identity. It also defines their limits.

In arguments with zealous New Atheist foot soldiers—most of whom, seem to know astonishingly little about the history and philosophy of science—one of the easiest ways to make them furious is to tell them that science can’t answer some of life’s great questions. You'll get accused of all sorts of things when you do this, usually of peddling ‘typical religious obscurantism’ or spouting ‘anti-scientific nonsense’.

As the writings of Richard Dawkins carry the status of Holy Writ for many of these very earnest people, we take pleasure in pointing out how Dawkins himself correctly emphasizes the moral limits of science: ‘science has no methods for deciding what is ethical’. This does, I have to say, throw them into some confusion. They often don’t know very much about Richard Dawkins either.

The clumsy word ‘scientism’—often glossed as ‘scientific imperialism’—is now used to refer to the view that science can solve all our problems, explain human nature or tell us what’s morally good. It claims that all that’s known or can be known is capable of verification or falsification using the scientific method. Anything that cannot be verified or falsified in this manner is to be regarded as at best mere private opinion or belief and at worst delusion or fantasy. Very few natural scientists embrace scientific imperialism, to my knowledge. It appears to appeal to a handful of philosophers on the one hand and a much larger cohort of adherents of popular ‘scientific atheism’ on the other.

Two areas of thought that clearly lie beyond the legitimate scope of the natural sciences are the non-empirical notions of value and meaning. These cannot be read off the world or measured as if they were constants of nature. As the philosopher Hilary Putnam rightly notes, while there’s such a thing as ‘correctness in ethics’, it’s important not to model our ethical thinking ‘on the ways in which we get things right in physics’.

The clumsy word ‘scientism’—often glossed as ‘scientific imperialism’—is now used to refer to the view that science can solve all our problems, explain human nature or tell us what’s morally good. It claims that all that’s known or can be known is capable of verification or falsification using the scientific method. Anything that cannot be verified or falsified in this manner is to be regarded as at best mere private opinion or belief and at worst delusion or fantasy. Very few natural scientists embrace scientific imperialism, to my knowledge. It appears to appeal to a handful of philosophers on the one hand and a much larger cohort of adherents of popular ‘scientific atheism’ on the other.

Two areas of thought that clearly lie beyond the legitimate scope of the natural sciences are the non-empirical notions of value and meaning. These cannot be read off the world or measured as if they were constants of nature. As the philosopher Hilary Putnam rightly notes, while there’s such a thing as ‘correctness in ethics’, it’s important not to model our ethical thinking ‘on the ways in which we get things right in physics’.

It’s been known since the eighteenth century that there are formidable intellectual obstacles in the way of anyone wanting to argue that science can generate moral values, most notably the impossibility of arguing from observed facts to moral values.

The New Atheist celebrity Sam Harris has tried to argue otherwise in his most recent book, The Moral Landscape.

The New Atheist celebrity Sam Harris has tried to argue otherwise in his most recent book, The Moral Landscape.

Moral values are about promoting human wellbeing. Since science tells about what promotes wellbeing, it can determine moral values. There’s no need for God or religion. Science can tell us what’s right. So what of the massive problems that philosophers know are associated with this kind of approach?

Harris deals with these by kicking them into the long grass, hoping that nobody who knows anything about the debate will notice his failure to engage with these problems. In the interests of reaching a ‘wider audience’, Harris avoids precisely the serious philosophical discussion that his position demands. The outcome is a lightweight and seriously deficient view of the foundations of morality.

Many atheist colleagues had hoped that Harris would stop ranting against religion and do some serious positive thinking instead. The New Atheism, in their view, desperately needed to show that it could do something other than rage against faith. Sadly it looks as though Harris just can’t break the habit. A whole chapter is needlessly given over to anti-religious polemic when it should have been used to deal with precisely the objections to his own position that Harris so badly needed to engage. The New Atheism is great at anti-religious rhetoric, but it’s yet to show that it can put forward a positive and defensible alternative to faith-based values.

Religion engages with questions that lie beyond the scope of the scientific method—such as the existence of God, the meaning of life and the nature of values. These are all open to rational debate; it’s very doubtful whether they’re open to scientific analysis in that they’re not empirical notions. I find myself in broad agreement with the conclusions of Sir Peter Medawar (1915–97), who won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on immunology. Medawar draws a distinction between ‘transcendent’ questions, which he thought were best left to religion and metaphysics, and questions about the organization and structure of the material universe.

Many atheist colleagues had hoped that Harris would stop ranting against religion and do some serious positive thinking instead. The New Atheism, in their view, desperately needed to show that it could do something other than rage against faith. Sadly it looks as though Harris just can’t break the habit. A whole chapter is needlessly given over to anti-religious polemic when it should have been used to deal with precisely the objections to his own position that Harris so badly needed to engage. The New Atheism is great at anti-religious rhetoric, but it’s yet to show that it can put forward a positive and defensible alternative to faith-based values.

Religion engages with questions that lie beyond the scope of the scientific method—such as the existence of God, the meaning of life and the nature of values. These are all open to rational debate; it’s very doubtful whether they’re open to scientific analysis in that they’re not empirical notions. I find myself in broad agreement with the conclusions of Sir Peter Medawar (1915–97), who won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on immunology. Medawar draws a distinction between ‘transcendent’ questions, which he thought were best left to religion and metaphysics, and questions about the organization and structure of the material universe.

Medawar insists that it’s ‘very likely’ that there are limits to science, given ‘the existence of questions that science cannot answer, and that no conceivable advance of science would empower it to answer’. Medawar makes it explicitly clear that he has in mind questions such as: ‘What are we all here for?’ ‘What’s the point of living?’ These are real questions and we’re right to seek answers to them. But science—if applied legitimately—isn’t going to help. We need to look elsewhere.

The New Atheism sees science as some kind of one-way intellectual superhighway to atheism. It’s not. Science can be made to resonate with atheism just as it can be made to resonate with Christian belief. It may certainly challenge some religious approaches that claim to offer a ‘scientific’ view of things. But in itself and of itself science is theistically neutral—unless it abandons the scientific method and strays into the more speculative world of metaphysics.

McGrath, A. (2011). Why God Won’t Go Away: Engaging with the New Atheism (pp. 77–80). London: SPCK.

The New Atheism sees science as some kind of one-way intellectual superhighway to atheism. It’s not. Science can be made to resonate with atheism just as it can be made to resonate with Christian belief. It may certainly challenge some religious approaches that claim to offer a ‘scientific’ view of things. But in itself and of itself science is theistically neutral—unless it abandons the scientific method and strays into the more speculative world of metaphysics.

McGrath, A. (2011). Why God Won’t Go Away: Engaging with the New Atheism (pp. 77–80). London: SPCK.