Is penal substitution cosmic child abuse?

|

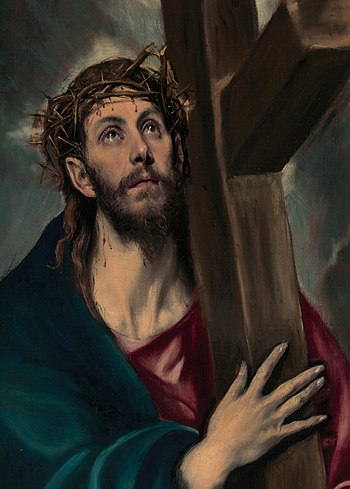

| ( ) (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The book is divided into two parts—the first making the positive case for penal substitution on biblical, theological, pastoral, and historical grounds, and the second outlining and answering objections that have arisen against the doctrine. While the authors acknowledge that there have been critics of penal substitution throughout church history, many of those critics have self-confessed outside the boundaries of evangelicalism and have largely been relegated to the upper echelons of academia.

However, recent critics of the doctrine not only regard themselves as evangelicals committed to the authority of Scripture, but are also finding their material published in more popular and mainstream Christian literature—not the least of which works has been Steve Chalke and Alan Mann’s The Lost Message of Jesus, which styles penal substitution as “cosmic child abuse.” Given that penal substitutionary atonement “stands at the very heart of the gospel” (21), such attacks have resulted in the “confusion and alarm among Christians” (25), which makes such a treatment necessary.

The authors begin by defining penal substitution as God’s giving of “himself in the person of his Son to suffer instead of us the death, punishment and curse due to fallen humanity as the penalty for sin” (21, 103). From here, they launch into a full-orbed, quasi-exhaustive biblical case for the doctrine, examining such key Old Testament passages as the redemption accomplished in Exodus 12, the atoning sacrificial system which reaches its apex in Leviticus 16, and the account of the Suffering Substitute in Isaiah 53.

The authors begin by defining penal substitution as God’s giving of “himself in the person of his Son to suffer instead of us the death, punishment and curse due to fallen humanity as the penalty for sin” (21, 103). From here, they launch into a full-orbed, quasi-exhaustive biblical case for the doctrine, examining such key Old Testament passages as the redemption accomplished in Exodus 12, the atoning sacrificial system which reaches its apex in Leviticus 16, and the account of the Suffering Substitute in Isaiah 53.

They also discuss the relevant New Testament texts, such as selected passages from Mark and John’s gospels, Paul’s letters to the Romans and Galatians, and Peter’s first letter to the churches. In so doing they provide a great foundation for the biblical-theological discussion that follows in chapter 3.

Sound exegetical reasoning throughout models how theology must be built on biblical exegesis. Word studies on key terms such as kipper (44–46), hilasterion/hilaskomai (82–85), andhuper (75–77, 98) provide biblical foundation for their theology, grounding their conclusions upon the solid rock of God’s Word.

Sound exegetical reasoning throughout models how theology must be built on biblical exegesis. Word studies on key terms such as kipper (44–46), hilasterion/hilaskomai (82–85), andhuper (75–77, 98) provide biblical foundation for their theology, grounding their conclusions upon the solid rock of God’s Word.

Further, their effective use of rhetorical questions patiently walks the reader through his own reasoning process in such a way that he understands the “theo-logic,” if you will, of this doctrine: Why should Jesus drink the cup of God’s wrath reserved for the wicked? Because He gives His life as a ransom for many (Mark 10:45; cf. pp. 69–71). Why should the sinless Messiah be cursed by God? Because He bore the curse due sinners to be their Substitute (Gal 3:10–14; cf. p. 89). A helpful summary concludes their biblical case:

The Bible speaks with a clear and united witness. Christ our Passover lamb has been sacrificed. The Servant was pierced for our transgressions. He died, as Caiaphas prophesied, in the place of the people. He was set forth as a propitiation for our sins. He became a curse for us, bearing our sins in his body on the tree, drinking for us the cup of God’s wrath, giving his life as a ransom for many. (99)

As mentioned, chapter 3 provides an overview of redemptive history and seeks to locate penal substitution in the context of the biblical-theological “jigsaw puzzle,” as they refer to it. While I might quibble with the authors’ styling man’s fall into sin as “decreation” (110), viewing the doctrine in light of the story of redemption allows the reader to discover how penal substitution “upholds the truthfulness and justice of God: it is the means by which he saves people for the relationship with himself without going back on his word that sin has to be punished” (137).

In this chapter the authors also address two helpful peripheral issues that are germane to the discussion. First, they insightfully note that Aulen’s Christus Victor theory of the atonement is true as far as it goes, but ultimately “fails to explain adequately how the victory is won” (139). Secondly, I appreciated their casting the effects of sin and the benefits of redemption inboth judicial and relational categories (136, 142–43). So often discussions of the forensic and legal nature of penal substitution can treat salvation as if it were solely a transaction. Jeffrey, Ovey, and Sach avoid such a one-sidedness by noting that it was not merely the death penalty or raw exercise of wrath that Jesus endured, but that that wrathful punishment included Jesus’ relational [note: not ontological] separation from His Father that we all deserved to endure for eternity. Such an understanding gets the dynamics of the Gospel right.

The authors reveal their true colors as shepherds when they address penal substitution from a pastoral angle. Often the doctrine is attacked on the grounds that it is simply grossly offensive to people and is uncharacteristic of a loving God. Yet our trio shows that penal substitution is the means to God’s love for man. They are right in noting that “love means different things to different people, and it can be hard to separate the biblical wheat from the sentimental chaff” (151). If we fail to understand the implications of Jesus Christ sent by the Father to become our sin-bearing substitute, we do not understand divine love (1 John 3:16; 4:8, 10).

The Bible speaks with a clear and united witness. Christ our Passover lamb has been sacrificed. The Servant was pierced for our transgressions. He died, as Caiaphas prophesied, in the place of the people. He was set forth as a propitiation for our sins. He became a curse for us, bearing our sins in his body on the tree, drinking for us the cup of God’s wrath, giving his life as a ransom for many. (99)

As mentioned, chapter 3 provides an overview of redemptive history and seeks to locate penal substitution in the context of the biblical-theological “jigsaw puzzle,” as they refer to it. While I might quibble with the authors’ styling man’s fall into sin as “decreation” (110), viewing the doctrine in light of the story of redemption allows the reader to discover how penal substitution “upholds the truthfulness and justice of God: it is the means by which he saves people for the relationship with himself without going back on his word that sin has to be punished” (137).

In this chapter the authors also address two helpful peripheral issues that are germane to the discussion. First, they insightfully note that Aulen’s Christus Victor theory of the atonement is true as far as it goes, but ultimately “fails to explain adequately how the victory is won” (139). Secondly, I appreciated their casting the effects of sin and the benefits of redemption inboth judicial and relational categories (136, 142–43). So often discussions of the forensic and legal nature of penal substitution can treat salvation as if it were solely a transaction. Jeffrey, Ovey, and Sach avoid such a one-sidedness by noting that it was not merely the death penalty or raw exercise of wrath that Jesus endured, but that that wrathful punishment included Jesus’ relational [note: not ontological] separation from His Father that we all deserved to endure for eternity. Such an understanding gets the dynamics of the Gospel right.

The authors reveal their true colors as shepherds when they address penal substitution from a pastoral angle. Often the doctrine is attacked on the grounds that it is simply grossly offensive to people and is uncharacteristic of a loving God. Yet our trio shows that penal substitution is the means to God’s love for man. They are right in noting that “love means different things to different people, and it can be hard to separate the biblical wheat from the sentimental chaff” (151). If we fail to understand the implications of Jesus Christ sent by the Father to become our sin-bearing substitute, we do not understand divine love (1 John 3:16; 4:8, 10).

We must behold the unseemliness of outpoured wrath in order to appreciate the loveliness of forgiveness, for “if we blunt the sharp edges of the cross, we dull the glittering diamond of God’s love” (153). Besides demonstrating God’s love, penal substitution also certifies God’s faithfulness. He has promised to punish sin, and “if God refused to break his word in this most extreme of cases [by punishing His innocent Son], we can trust him in every other situation. The torment of the cross “stands as a monument to the unchanging truthfulness of God’s word” (156). Indeed, “far from being the cause of many pastoral problems, penal substitution is frequently the cure” (321).

After a surveying the undeniable support of penal substitution through church history, the authors “outline all of the major objections to the doctrine of penal substitution that [they] have encountered” (206). The exhaustiveness of their defense coupled with a helpful, well-structured format—in which the authors state an objection from primary source literature and offer a clear response—makes this book an invaluable reference work. The authors ably and patiently deal with objections on the grounds of biblical interpretation, culture, violence, justice, theology proper, and the Christian life.

After a surveying the undeniable support of penal substitution through church history, the authors “outline all of the major objections to the doctrine of penal substitution that [they] have encountered” (206). The exhaustiveness of their defense coupled with a helpful, well-structured format—in which the authors state an objection from primary source literature and offer a clear response—makes this book an invaluable reference work. The authors ably and patiently deal with objections on the grounds of biblical interpretation, culture, violence, justice, theology proper, and the Christian life.

In each of these cases the objections are decisively refuted in a clear and cogent manner. Apart from merely listing the objections and the authors’ astute responses, there is little more to add by way of evaluation than to say that no objection to penal substitution stands in the light of Jeffrey, Ovey and Sach’s scriptural scrutiny. At all points I found myself in hearty agreement with their presentation. Perhaps it will suffice to note a particularly helpful response given while discussing particular redemption. The authors insightfully remark that the word “all” often indicates “all without distinction” rather than “all without exception” (274). Thus one might affirm that Christ died for all, if by that one means that Christ died for all kinds of people, and not that Christ bore the Father’s wrath as a Substitute for every single individual who ever lived.

Pierced for Our Transgressions has accomplished precisely what the authors have aimed to do. In this work, evangelicals hold in their hands a robust case for the doctrine of penal substitution—considered biblically, theologically, pastorally, and historically—alongside an exhaustive defense of the doctrine from naysayers old and new. Jeffrey, Ovey, and Sach have provided a thorough, measured, scholarly work that nevertheless avoids the technicality of the academic elite and remains accessible for those interested in the doctrine of the atonement.

Pierced for Our Transgressions has accomplished precisely what the authors have aimed to do. In this work, evangelicals hold in their hands a robust case for the doctrine of penal substitution—considered biblically, theologically, pastorally, and historically—alongside an exhaustive defense of the doctrine from naysayers old and new. Jeffrey, Ovey, and Sach have provided a thorough, measured, scholarly work that nevertheless avoids the technicality of the academic elite and remains accessible for those interested in the doctrine of the atonement.

I would heartily recommend it as a superb reference work for those desiring a defense of penal substitution, or who are interested in the biblical, theological, and historical development of the atonement. Author: Cripplegate